Perhaps a good hotel is safest place to stay in a war zone even if the rooms do have notices advising guests what to do ‘on hearing the rockets, mines or projectiles coming in towards the hotel’. See The Times report from the Ukraine below.

Perhaps a good hotel is safest place to stay in a war zone even if the rooms do have notices advising guests what to do ‘on hearing the rockets, mines or projectiles coming in towards the hotel’. See The Times report from the Ukraine below.

Grace under fire at the Ramada hotel in Donetsk

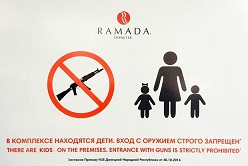

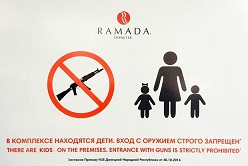

The sign at the Ramada alerting guests to the gun ban

Ben Hoyle/The Times

The sign at the Ramada alerting guests to the gun ban Ben Hoyle/The Times

Ben HoyleDonetsk

Last updated at 12:01AM, February 16 2015

Even when there are no gunmen outside, the sign on the doors of the Ramada hotel in Donetsk reminds you that you are somewhere unusual. There’s a picture of a Kalashnikov automatic rifle with a red line through it next to a simple image of a woman with her son and daughter and the message: “There are kids on the premises. Entrance with guns is strictly prohibited.”

It needed saying. Back in the summer, when the city first came under artillery attack, there were far, far too many separatist fighters drinking beer and clowning around with loaded AK-74s on the Ramada’s pleasant veranda.

Evening firearms etiquette seems to have improved though. The cold weather has driven everybody inside now. but the Ramada’s restaurant — used by reporters, aid workers, mafia types, overdressed women and separatist fighters — remains a source of indispensable up-to-date knowledge about what is happening in the conflict zone.

It’s also almost possible to forget the war in there. A late-1970s French disco album plays very loudly, drowning out the rocket fire outside. There are cocktails, shisha pipes and good coffee. The chef has concocted a menu of Russian cuisine based on 19th-century recipes. I recommend beef cheeks.

In the hotel trade, of course, it’s the little things that count. Like the note in every room explaining what to do “on hearing the rockets, mines or projectile coming in towards the hotel”. Broadly: get down and stay down. The same action is “also necessary to do when hearing shooting by an automatic weapon nearby the hotel”.

The staff still replace those tiny bottles of shampoo. Wi-fi has, by and large, been superlative. The swimming pool is open, though it did close in August when the city water supply briefly seized up.

It’s not just reporters who appreciate the Ramada staying open. Many of the remaining staff and their families have moved in too — the children mentioned in the sign on the door. In a city drained of jobs and exposed to daily attacks the Ramada offers its employees a salary and better shelter than in most of the suburbs.

Every conflict and revolution throws up memorable examples of the hospitality industry’s resourcefulness, courage and grace under fire, and the Ukraine crisis has been no exception.

To start there were the three Kiev hotels that found themselves inside the protesters’ ring of barricades during the Maidan demonstrations that toppled President Yanukovych a year ago this week.

The story moved to Crimea, where the grand terrace of the Best Western in Sevastopol commanded an impressive view of what rapidly became Russian waters. Hotel space in the Crimean capital of Simferopol was at a premium for months, filled at first with the press and then with Russian businessmen, so a special mention to the Hotel Marakand, a Crimean Tartar place where I found the outspoken political leader of the Crimean Tartars who I’d been trying to interview for weeks. He was living in a top-floor room near mine and had hung a flag over the corridor window to foil assassination attempts, which was great.

Nowhere, though, has said “home” like the Ramada in Donetsk. Last week I bumped into Alexander Georgievich, the franchise owner, in his lobby. A large, bearded man with flowing dark hair and a startling wardrobe of bright jackets and ties, he vowed that “even if they drop a bomb here we will never leave this place”. He had to run to talk to some rebel fighters but added, with a smile: “In stressful times you can see the worst of people, and the best.”

http://www.thetimes.co.uk/tto/news/world/europe/article4354944.ece